Etruscan goddess of battle, Bellona.

Bellona was thought to be the feminine equivalent of Mars, the god of battle, by ancient Italians.

- In early Rome, she was portrayed as a woman with a sword, spear, and torch, and she had her own temple.

In Ostia Antica, there is a temple or sacellum called Bellona that is devoted to the Italic goddess Bellona, who may have been combined with Magna Mater in this instance.

It is made up of a modest structure with a cella that is preceded by two columns and three frontal steps, and it is located on the east side of the "Campo di Magna Mater" (Regio IV, Insula THE, n. 4).

The whole structure is composed of brick, including the columns. A modest platform at the rear of the cella, frescoed walls, a white mosaic floor, and a marble threshold with holes for the door pivots are all features within.

A relief depicting two pairs of feet looking in opposing directions was discovered in the temple; it may have been a votive gift from a soldier who had left for battle and returned home safely.

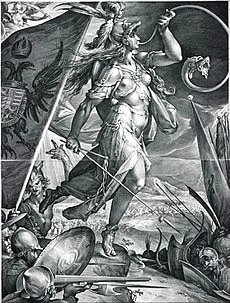

She usually rides into combat in a four-horse chariot while brandishing a sword, spear, shield, torch, or whip as her most distinguishing feature.

All around the Roman Empire, she had several temples.

She is renowned for her ferocity and insanity in combat as well as for having her temple outside of Rome serve as the official war decision-making location. After the Renaissance, sculptors and painters added to her iconography.

The name of the goddess of battle Bellna comes from an older Duellona, which was derived from the word duellum (which meant "war, fighting" in Old Latin) and the word bellum (which meant "war" in Classical Latin).

Duellum's derivation is still a mystery. A derivation from *duenelo-, a reconstructed diminutive of the word duenos that is found on an eponymous inscription as an early Old Latin precursor of the word bonus ('excellent,') has been hypothesized by linguist Georges-Jean Pinault.

In the context of battle (bella acta, bella gesta), the usage of *duenelo- "may be viewed as a euphemism, finally producing a meaning 'activity of courage, war' for the word bellum," according to linguist Michiel de Vaan.

Bellona was initially a Sabine goddess of battle who was linked to Nerio, Mars's war partner, and then to Enyo in Greek mythology. During the conflict with the Etruscans and Samnites, Appius Claudius Caecus erected her temple at Rome in 296 BCE, next to the Circus Flaminius.

The first site where ornamental shields intended for mortals were hung in a sacred space was this temple. The shields were hoisted and given to Appius Claudius' family.

Her feast was held on June 3, and her priests, known as Bellonarii, offered blood sacrifices to her by cutting off their own arms or legs. Following the event, these ceremonies were performed on March 24, also known as the Day of Blood (dies sanguinis). Enyo and Bellona both associated with her Cappadocian aspect, Ma, as a result of this ritual, which was similar to the Cybele-dedicated ceremonies in Asia Minor.

Bellona's temple was located on the Roman Campus Martius, which enjoyed extraterritorial status. Foreign ambassadors who were prohibited from entering the city main lodged in this facility.

The Senate convened there with diplomats and welcomed triumphant generals before their victories since the temple's location was outside the pomerium.

The battle column (columna bellica), which symbolized non-Roman land, was located next to the temple. In a version of the ancient ritual, one of the priests involved in diplomacy (fetiales) would hurl a javelin over the column from Roman territory in the direction of the enemy country, and this symbolic attack was regarded as the beginning of war. Pyrrhus made this declaration of war against the first adversary in 280 BC.

Temples Dedicated To Goddess Bellona.

There were many eager to help in maintaining and enhancing her temples and shrines. They were also prepared to shoulder the expense themselves.

She was often worshiped in secret since she was seen to be a temperamental deity, and the majority of her followers chose to do so.

Rome is filled with signs of her adoration, despite their subtlety.

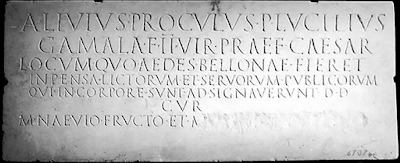

There have been discovered at least seven inscriptions that are connected to Bellona worship. An ancient inscription from the Forum of Augustus refers to the conflict with Pyrrhus.

The Aedem Bellonae (a temple dedicated to Bellona) is where five of the inscriptions were discovered, while the other two are destroyed.

But her veneration was not confined to Rome. As far north as York, England, where the modern St. Peter's Church is located, Bellona had a temple.

Worship Of Bellona.

The adoration of Bellona and the legends surrounding her were often graphic or frightful.

Discordia, Strife, and the Furies were said to follow her to battle, terrifying her adversaries. One of the most common ideas is the widespread acceptance of her bloodlust and lunacy in combat.

The Scordici people, according to Ammianus Marcellinus, practiced aggressive Bellona worship. They were vicious and ferocious in their worship of Bellona and Mars. Blood would be drawn from the victims' heads and offered up as human sacrifices.

She was linked to Virtus, the embodiment of valor, in the military cult of Bellona. She also accompanied the imperial forces on expeditions outside of Rome, and records of her temples in France, Germany, Britain, and North Africa exist.

Although the goddess Bellona occurs as a figure in Statius' Thebaid, symbolizing the destructive and belligerent part of battle, the term Bellona is often employed in poetry merely as a synonym for war.

There, she is represented as riding in a chariot and brandishing a bloody sword or holding a spear and fiery light. Shakespeare's plays subsequently include references to Bellona in the context of warrior characters.

For instance, Hotspur refers to the goddess as "the fire-eyed woman of smoky battle" and Macbeth is referred to as "Bellona's husband," which is another way of saying Mars.

Portrayal Of Goddess Bellona In Contemporary Works.

In more recent times, Adam Lindsay Gordon's poem "Bellona," which was published in Australia in 1867, was a passionate Swinburnean evocation of the "false goddess" who misleads mankind. She also appears in the World War I poem "The Traveller" by Arthur Graeme West.

In that passage, the poet depicts himself as advancing into the front lines with Pan, Art, and Walter Pater's works.

One by one, the amorous partners are compelled to flee before the fury of battle as they approach Bellona, until the goddess is ecstatic to have him to herself.

In the opera Les Indes Galantes (1735), Bellona makes an appearance in the prologue, when the call of love eventually prevails over the cry of battle. Tönet, ihr Pauken! was played in a Bach dramma per musica two years earlier. BWV 214's Erschallet, Trompeten, even sets aside her typical wrath to wish Maria Josepha of Austria, Princess Elector of Saxony, and Queen of Poland a happy birthday on December 8.

In "Prometheus Absolved" by Giovanni Ambrogio Migliavacca (1718-1795), she still has a nasty personality.

The deities sit in judgement on Prometheus in this cantata honoring the birth of the Archduchess Isabella in 1762, with some pleading for mercy and others demanding rigor. She also contributes appropriately to the "heroic cantata," "The Wedding of the Thames and Bellona," written by Francesco Bianchi and Lorenzo da Ponte (Le nozze del Tamigi e Bellona).

To commemorate the British naval victory against the Spanish at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, this performance took place in London (1797).

Depiction Of Goddess Bellona.

Bellona is often shown with a plumed helmet, armor, or at the very least a breastplate with a skirt below.

She holds a spear, a shield, or other weapons in her hand, and on occasion, she blows a trumpet to signal an assault.

She formerly had a connection with the winged Victory, whose statue she sometimes bears and who, when shown on battle monuments, holds a laurel crown in her hand.

Examples of this kind of armored figure may be seen in the 1633 Rembrandt painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as in the 1770 and 1805 sculptures by Johann Baptist Straub and Johann Wilhelm Beyer (1773–80). Since both were connected to the Roman traditions of declaring war, she appears in the latter with the deity Janus. In the instance of Janus, the temple's doors remained open throughout the conflicts.

Similar to the Rembrandt painting, Straub's statue (below) has a gorgon head on her shield to terrorize her adversaries; however, this was added later, perhaps in reaction to other instances of this new iconographical departure.

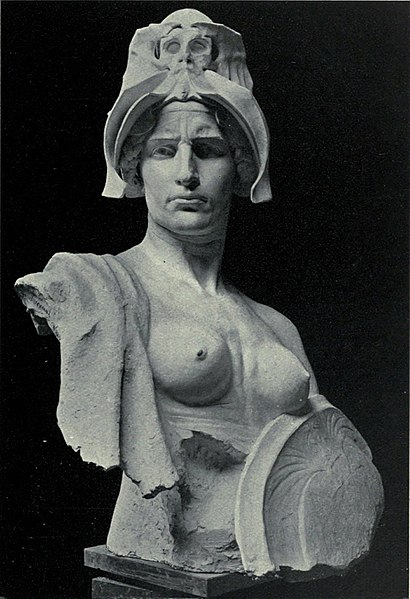

She carries a gorgon mounted on her helmet in Bertram Mackennal's bust, while in other representations, it is on the breastplate. In his glazed bust of the goddess, Jean-Léon Gérôme goes even farther in depicting the agony of battle (1892). She not only has a head around her neck, but her fearsome appearance, complete with screaming face and angular winged helmet, gives her the appearance of a gorgon.

Another popular innovation was the pairing of Bellona with cannons, as shown in the painting by Hans Krieg (1590-1645) and the ceiling fresco by Hans Georg Asam at Hammerschloss Schmidmühlen in 1700. (1649–1711).

An early Dutch etching picturing this goddess sitting in a manufacturing workshop with various weapons at her feet as part of a series of prints illustrating Personifications of Industrial and Professional Life claims that this goddess is the one who inspires the manufacture of war equipment (plate 6, see the Gallery below). Her picture is updated in the fresco by Constantino Brumidi in the U.S. Capitol (1855–60). The stars and stripes are seen on her shield as she stands next to an artillery piece in that image.

Not all depictions of Bellona are clad in armor. Both the Alvise Tagliapietra statue in St. Petersburg (about 1710) and the Augustin Pajou statue at the J. Paul Getty Museum (1775/85) are mostly nude, but they do carry or wear some of the goddess' other features.

However, there are allusions in classical literature that support this. For instance, the description "Bellona with naked flank, her brazen weapons rattling as she went" may be found in Gaius Valerius Flaccus' Argonautica (3. 60).

The painting "Bellona Presenting the Reins of his Horses to Mars" by Louis Jean François Lagrenée has another poetic allusion that a painter has used (1766). This is an illustration of a line from Claudian's In Ruffinum when Mars asks Bellona to bring his helmet and Terror to take the reins (Fer galleam Bellona mihi, nexusque rotarum tende Pavor). Poetic is another word for "Wisdom restraint Bellona," an allegorical painting by Jan van Mieris from 1685.

The helmeted goddess is turning to go with her cloak billowing behind her and her shield held high in her extended left hand when the sitting figure of Wisdom grabs her right hand.

Besides serving as decoration, images of the goddess also had a practical purpose for the general population. During the Long Turkish War, Austria actively participated in anti-Turkish propaganda with works like "Bellona Leading the Imperial Armies against the Turks" by Batholomaeus Spranger (see above).

Jean Cosyn's triumphal gateway in Brussels, today known as the Maison de Bellone, marks a later stage of the ongoing fight, which culminated in victory at the battle of Zenta in 1697. At its center, the goddess is a helmeted figure surrounded by military flags and cannons.

Peter Paul Rubens' "Marie de Medici as Bellona" (1622/5), which was created for her public spaces at the Luxembourg Palace, makes a dynastic political statement. He portrays her as exercising political influence there at a time when it had, in reality, diminished.

She is armed with muskets, cannons, and armor, and symbols of victory serve to emphasize her victories. She holds a little statue of the winged goddess in her right hand, and behind the helmet's plumes, a smaller winged figure is mounted. Cupids are hovering above her, each clutching a laurel crown.

Her representation stands in stark contrast to Rembrandt's painting of Bellona, which displays the unremarkable features of a typical Dutchwoman. With the promise that the new Dutch Republic is prepared to defend itself during the Thirty Years' War, notably against Spain, this makes an anti-imperial stance.

The Bellona head sculpture by Auguste Rodin (1879), which exudes even greater hostility, was initially intended for a monument honoring the French Third Republic.

The head is pulled back in prideful rage, rotating in a dramatic movement to glance down the line of her right shoulder. This is modeled by his mistress Rose Beuret in a foul temper.

The Bellona fountain in Wuppertal by Georg Kolbe conveys the idea of defense in times of conflict. It featured the helmeted goddess motivating a young man who was kneeling and holding a sword in her left hand when it was first commissioned in 1915. It wasn't until 1922 that the statue was built, at which point it served as a war monument.

Prior to this, Bellona's employment in such constructions was widely documented because of how prominently she appeared in Jean Cosyn's entryway.

A monument honoring the Anglo-Hanoverian military effort during the Seven Years' Conflict, the Temple of Bellona was created by William Chambers for Kew Gardens in 1760. Eventually, it featured plaques honoring the regiments that participated in the war. However, they were more focused on remembering victories than lost loved ones.

A monument in Quebec was not erected to honor the French-Canadian Seven Years War casualties until a century had passed. Bellona stands atop a large column on the battlefield, looking down while holding a shield and laurel crown in her right hand. In 1862, Jérôme-Napoléon made a gesture of peace by presenting the monument.

Bertram Mackennal, a former pupil of Rodin, created a bronze bust of Bellona to honor the Australian casualties during the Gallipoli Campaign. In 1916, he gave this as a monument to the Australian government in Canberra.

The helmeted head is tilted to the right, like in Rodin's bust, but the breasts are more noticeable. In places like this where Bellona is prevalent, the fallen often arrive later.

In Douglas Tilden's monument to the California Volunteers during the Spanish-American War at 1898, they stand behind the goddess brandishing a sword; in the Bialystok memorial to the slain in the Polish-Soviet War in 1920, she is positioned behind a soldier and is holding aloft a laurel crown.

However, the Bellona on the Waterloo station triumph archway from the First World War stands out. Not the dead, but the forgotten live victims of war, crouch and grieve under the demonic sword-wielding wraith with her gorgon necklace.