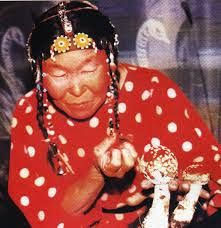

Siberian mother of animals, Bugady Musun.

Bugady Musun is the ruler of all life and food, as well as the protector of all creatures and nature.

- She is shown as an elderly yet brawny lady who protects and guides vets.

- She is a shapeshifter who may appear as a reindeer or an elk to her petitioners.

Bugady Musun is a Siberian divinity who was especially adored by the Evenki.

She was the protector of animals and the patron of nature.

She was generally a fierce elderly lady or a massive female elk or reindeer.

Many Siberian peoples worship this deity.

Bugady Musun was the protector of animals and the patron of nature.

The antlerless female elk (a symbol for the ever-renewing source of human nutrition) and a boat initially appeared in the Baykal Neolithic era as the deer (a metaphor for the passage of the soul into another world after death).

The Baykal Neolithic elk vanished in the late third or early second millennium BC (the Bronze Age), and a new group of representations (bull, cattle, deer, people in different ceremonial situations, cartwagon-wheeled vehicles) arose in South Siberia.

The female elk was replaced with a clearly female half-human, half-animal creature, who subsequently returned as a cow.

As a cow, this picture came from a tradition that had previously crowned her horns, and as a deer, it came from a northern tradition that had previously given her an elk's body.

Her indications and location as a woman connected her with life and death (at the Minusinsk monoliths, for example, this is expressed by the stones being rooted in the ground-the vertical axis-and their masks aligned towards the east).

On the higher reaches of the major Siberian rivers, Neolithic sanctuaries with petroglyphs such as the Baykal female elks have been discovered, as have Bronze Age ceremonial sites erected in large valleys surrounded by mountains.

Such a shift reflects a shift from relying on forest and river hunting and fishing to relying on pasture-based cattle farming.

Mongolia, the Sayan Altai Ridge, and the Minusinsk Basin formed a prominent cosmos during the Bronze Age.

There was a relationship with the Indo-European legendary tradition of a solar chariot and warriors in relation to the contemporaneous appearance of bull and cart representations in South Siberia.

Similarities between Yamna-Afanashevo (pit-grave) and Shrubnaya-Andronovo (timber-grave) civilizations are to blame for such alterations.

People with Indo-European heritage gradually migrated from the west and southwest into northern Kazakhstan, northern Altay, and Mongolia.

The elk continued to dominate late Bronze Age imagery in the shape of a deer, which was carved on rock walls and boulders, as well as around monolithic people in different ceremonial contexts.

This occurred in South Siberia and Mongolia around the first millennium BC.

The phenomena is particularly relevant to the region's so-called deer stones, and it complicates their interpretation.

There are two kinds of stones like this.

The Mongolian and Transbaykalian types, which feature deer in a recumbent position with exaggerated antlers, beak-like heads, graceful necks and bodies, short triangulated forelegs, and truncated hindlegs, are more common in Sayan-Altay.

We see carved chains of beads around the stone's neck, three parallel slanted lines at the side of the face, carved markings that seem like earrings, and a carved belt with hanging weapons or tools on both kinds of stones.

Carved depictions of animals, including deer, boar, horses, caprid, and crouching feline or wolf-like creatures, fill the gaps in between.

Wecan further examine what is known as the semantics of the deer stones, based on archeological data.

We can cast doubt on the widely held belief that the deer stones are linked to the Indo-European legend of an original masculine hero (a male warrior).

Comparisons of the Siberian stones' hanging instruments to the so-called Cimmerian Stelae and Scythian Baba seem to have led to the conclusion that they depict males, maybe even males as hunters or warriors.

Despite the presence of the hanging weapons/tools, no signs of belligerence are there.

These forms may be traced back to the Early Nomads' older symbolic forms, and that at least one of the three images central to the Scytho-Siberian artistic heritage came from South Siberia (the deer, the coiled feline, and a wolf-like animal).

The presence of weapon-like objects, as well as the correlation of these stones with the image of the deer, has led to the belief that the deer is a symbol for the warrior.

It is based on a connection between the masculine warrior and a solar complex of deer, gold, and horse.

This solar relationship did not always exist, and the figure was more likely feminine in character, which is why it was associated with the image of a deer during the Early Nomads period.

We can analyze the culture and mythology of the Paleo-Siberian Ket and the Tungusic Evenk in an effort to rebuild ancient mythological and ceremonial symbolic systems, considering this to be the richest and most important source for this purpose.

The Ket concept

The Ket concept of the Khosedam/Toman duality, as well as the Evenk concepts of Bugady Mushunin, "the mistress of the clan," and bugady enintyn, "the mistress-mother of the clan" (both combining the idea of woman and cow elk or wild cow reindeer [half-human, half-animal]), as well as beliefs and rituals associated with those deities.

To bridge the gap between archeological and ethnographic data, we can make many hypotheses and suggestions.

When it comes to the origins of shamanism, it is premature to explain the archeological traces of Siberian Neolithic, Bronze, and early Iron Age cultures with reference to shamanic practices that are only known from recent times, given that our evidence for the existence of shamanic institutions consists primarily of petroglyphic images of masks or horned figures.

The shaman's ability to complete the shamanic journey is reliant on items such as a drum that serves as the shaman's steed; a robe with a headdress adorned with imagery and amulets that simultaneously protect, empower, and transform the shaman; and, finally, a vertical axis, real or imagined, that serves as a pole linking the underworld, earth, correlating the signs and symbols connected with the shaman with the indicators of a trip beyond death found in Early Nomadic graves reveals that power was shifted from the early Iron Age.

Furthermore, the poems detailing the shaman's trip, as well as the voyage itself, have clear connections with zoomorphic imagery from the Early Nomads' time.

Despite this, the parallelism is just suggestive.

Early Nomads' Deer Image.

The elaborate stone structures of the Early Nomads, as well as the enigmatic symbolic structures with which they laid their dead and their horses to rest, were the result of a process reflected in the Ket and Evenk mythic traditions and enclosing most archaic layers that continued through millennia.

Beginning with Ninhursag and concluding with Anahita/Nana, we can delve into the Pontic Scythian legendary legacy as told by Herodotus, as well as the greater history of Near Eastern goddesses.

The Scytho-Siberian aesthetic tradition in its ceremonial framework, as well as Siberian mythological traditions are seen in ethnography.

From this evidence that the Early Nomads' deer image, which they inherited and expanded into the heart of their symbolic systems, represented an ecosystem of belief.

Predatory animals were followed by the deer, which joined the Age of the Early Nomads as a reclining (or, more rarely, a standing) beast.

Predatory animals were then rejected due to an increased preoccupation with human iconography and realism.

The Deer As A Woman.

The deer took on the appearance of a lady sitting before a man carrying a rhyton towards the conclusion of the Scytho-Siberian era (see for instance the North Pontic Chertomlyk, Karagodeuashk, the Merzhany plaques, the figures of the Prigradnaya "Scythian Baba," and the felt hanging from Altay Pazyryk).

However, it was eventually overshadowed as a woman, with only a male figure referring to her.

The deer was destined to survive solely via Siberian and Central Asian shamanic traditions when Scytho-Siberian society vanished.

The deer picture provides evidence for the birth and eventual extinction of a genuinely Siberian cosmogonic source: the Animal Mother, the source of life and death, rather than a solar hero or Indo-European ideals.

References And Further Reading

- Jacobson, E., 2018. The deer goddess of ancient Siberia: a study in the ecology of belief. Brill.

- Fitzhugh, W.W., 2009. Stone shamans and flying deer of northern Mongolia: Deer goddess of Siberia or chimera of the steppe?. Arctic Anthropology, 46(1-2), pp.72-88.

- Bleeker, C.J., 1975. The Rainbow: a collection of studies in the science of religion (Vol. 30). Brill Archive.

- Shigehiko, F., 1996. The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia: A Study in the Ecology of Belief.

- Francfort, H.P., 1993. The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia. A Study in the Ecology of Belief (Studies in the history of religions [Numen Book Series] vol. LV).

- Champouillon, L., 2012. Varieties of Deer Imagery: Gender and Cosmology in Prehistoric Belief Systems of Central Asia and South Siberia.

- Fitzhugh, W.W., 2009. The Mongolian Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex: Dating and Organiation of a Late Bronze Age Menagerie. Current arc

- Boucherit, G., 2011, August. A deer cult in Buile Suibhne. In XIV COMHDHÁIL IDIRNÁISIÚNTA SA LÉANN CEILTEACH XIV INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF CELTIC STUDIES.

- Lymer, K., Fitzhugh, W. and Kortum, R., 2014. Deer Stones and Rock Art in Mongolia during the Second to First Millennia BC. Deer and People, p.159.

- McFarland, R. and Schalaben, W., 1995. Placentas and Prehistoric Art. The Journal of Psychohistory, 23(1), p.41.

- TATAR, S., The Legend of the Palóc Prince of Göcsej: Images of Bridled Deer and Antlered Horses. Cosmos: the yearbook of the Traditional Cosmology Society.

- Diószegi, V. and Rajkay Babó, A., 1968. Tracing shamans in Siberia: the story of an ethnographical research expedition.