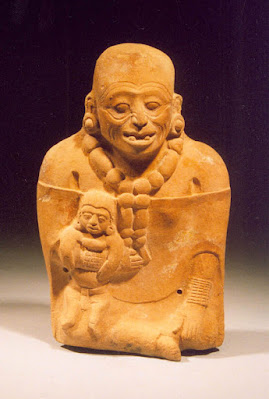

Mesoamerican Goddess of childbirth, Akhushtal.

- Akhushtal is the Mayan god that oversees the whole process of childbirth, from conception to delivery.

- Akna was a term given to Akhushtal, among other goddesses, that meant 'Our Mother,' and was strongly tied with fertility and birthing deities.

Mayan Midwifery And Society.

Midwifery is a female-dominated profession that aids women from conception until postpartum care.

Akhushtal goddess of midwifery is worshipped in certain Maya tribes, and midwives are said to be allocated their vocation via signs and visions.

Ixchel was the name of the pre-Spanish Yucatan deity of the old midwife.

Childbirth is the Maya's ultimate rite of passage, completing a girl's transformation to womanhood.

Many women who give birth in remote regions are cared for by midwives who have no official training but are said to have gotten instruction in dreams by the Maya religion.

Traditional birth attendants are referred to as comadronas or iyom kexelom, and their work is regarded with respect.

Maya midwives are in charge of the ajtuj ("pregnant lady") and her unborn child during the pregnancy as well as the week of bed rest after the delivery.

Unlike other communities, the Maya believe that they receive a holy calling from God via dreams, allowing them to perform their intended career.

The midwife's calling is divine, and she has the ability to speak with the supernatural realm.

Though midwives are revered for their holy role in society, they sometimes face animosity from their spouses and children since they must spend so much time away from them in order to do their duties.

Midwives are required to refrain from sexual activity, which might cause conflict with their spouses.

Midwives are said to acquire their calling from God via a sequence of dreams in Maya civilization.

Visions of Saint Anne, the patron saint of all midwives, are said to often carry subtle signals that a woman is destined to become a midwife.

Women, according to the Mayan faith, discover little artifacts along routes that represent symbols and objects associated to midwifery, in addition to getting dreams and visions.

Small unique stones in the form of faces, shells, marbles, and shattered parts of prehistoric figures are common.

In Maya religion, stones are typically ascribed holy qualities and are said to be sent from the spiritual realm as a symbol of one's vocation to midwifery.

Some things placed in a midwife's path are said to be the instruments they require to execute aspects of the delivery process, such as a penknife for cutting the umbilical cord.

Women often contact shamans, who explain their calling to them, and if they accept their calling as midwives, they are said to have a series of dreams and visions about the birthing rituals they must follow.

They may also be called to mountains or other holy sites, where they may meet supernatural entities, in addition to these specific things and the repeated dreams.

Mayans think that women who disregard their calling are more likely to get sick, and that if physicians are unable to diagnose their diseases, they may even die.

They also think that supernatural creatures tell them in their visions that they will get presents from the families of the children they deliver, and that they must not be greedy since many will offer what they have, and that they must take it with a good heart.

Midwives are in charge of pregnant women throughout their pregnancies with no official training or education other than what they think they acquire through their dreams.

These dreams are said to include visions from the spirits on how to correctly inspect women, massage them, feel for the position of the fetus, measure dilation, cut the umbilical chord, pray, and prophesy a child's destiny based on the marks on their umbilical cord.

Midwives think that by seeing these visions, they will be able to recognize difficulties that might jeopardize a healthy birth and will be able to take women to local clinics and hospitals.

Midwives are called during the third to fifth month of pregnancy and provide prenatal care at monthly intervals until the last month of pregnancy, when they begin to visit weekly.

Midwives offer prenatal care that includes massages, exams, attending the delivery, and caring for both the new mother and infant during the week of bed rest.

Many things, according to the Mayans, may be interpreted when a child is born.

The "Sacred calendar," or Maya calendar for divination, is said to forecast a child's destiny since certain days are more favorable than others.

In Maya civilization, the calendar is crucial for understanding and determining the destiny of children.

Mayans, on the other hand, believe that midwives may predict a child's life based on the marks on the umbilical cord and the amniotic sac.

They think that the sex, number, and spacing of subsequent births may be predicted based on the marks of the firstborn.

The most essential marks are those of a future shaman (worms or flies gripped in a newborn's hand), a midwife (white mantle over the head, which originates from the amniotic membrane), and a baby who will imperil future siblings' life (born with a double whorl in its crown).

The midwife is the first person to view the newborn, and before a mother can connect with her kid, the midwife is supposed to carefully read the child's symptoms, and she alone will determine what career the child will pursue.

She must then carefully remove, dry, and conserve the signs, which the maternal grandma will maintain.

Praying is regarded crucial in the delivery of a child, and the midwife starts praying as soon as she is notified about the birth.

Before entering the home and touching the pregnant lady, she is also supposed to pray.

She must also pray to each of the room's four corners, which are thought to be guarded by unseen guardians.

When subsequent children die, one ritual must be completed because it is thought that the first-born child (sometimes born with a double whorl on the umbilical cord) pursues and consumes the newborn's soul.

The midwife wraps a live chicken in a cloth and travels the room with the eldest kid praying to each of the four corners in an attempt to preserve the newborn's life.

On the back of the oldest kid, the chicken is battered to death (behind closed doors and away from the newborn).

She then cooks a chicken soup, which the oldest kid is obliged to consume in its whole, even if it takes many meals.

The midwife must execute her last cleaning rites at the conclusion of the bed rest week, indicating the end of her duties.

The infant is washed, and a fresh dress is put on the naval, as well as the hammock in which the baby will sleep.

She requests that the infant be kept safe.

In a semi-public hair washing ritual, the mother is also purified.

Before she goes, the last ritual she must undertake is sweeping and cleaning the room.

She then says a last prayer, thanking the spirits for a safe delivery.

The Birthing Figure at Dumbarton Oaks is spectacular, dramatic, and completely unique.

The anguish and bliss of labor are perfectly captured in this Aztec-style sculpture of a lady giving birth.

It has long wowed spectators, including artists, researchers, and notable collectors of Pre-Columbian art, thanks to its excellent carving in a hard, speckled stone called aplite.

Its distinctive iconography and carving have provoked a heated discussion about its origins and validity.

The sculpture has been related to a portrayal of the goddess Tlazolteotl in the process of childbirth found in the Codex Borbonicus, which was first cited in an 1899 book by the French anthropologist E.T. Hamy.

This goddess, whose name means "eating of dirt," was linked to sexuality and the atonement of crimes.

She wears a big cotton headpiece with crescent-shaped decorations on her nose and/or garments in the codices.

Her mouth is filthy and stained.

The Birthing Figure sculpture is unique in that it lacks Tlazolteotl's typical characteristics.

Unlike any other Aztec god sculpture, this one is nude and unadorned.

Scholars have noted other unique aspects, such as the figure's crisp edges and immaculately straight hair, since the 1960s.

Some have speculated that the sculpture was not done by Aztec carvers.

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) study of the item in 2002 revealed that most of the carving was done using contemporary rotary tools.

The Dumbarton Oaks Birthing Figure was carved – or maybe re-carved – in the nineteenth century.

The history of the sculpture is interesting.

It travelled through various members of France's Academy of Sciences around the turn of the twentieth century, and was chronicled by anthropologist E.T.

Hamy, who prepared a plaster cast for the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro.

By the early 1930s, the figure had passed through the hands of Parisian art dealer Charles Ratton, who sold it to Joseph Brummer, a New York-based art dealer and collector.

Until his death in 1947, Brummer kept the artwork in his personal collection.

The Birthing Figure was purchased by Robert Woods Bliss, the creator of Dumbarton Oaks, at that time.

He exhibited it in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and then at the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection in Washington, D.C., beginning in 1963.

Many books, exhibition catalogues, and other media have included The Birthing Figure.

It's also sparked a slew of creative initiatives.

Man Ray, a surrealist photographer, made a four-part photomontage (about 1932) to emphasize the piece's dynamic lines.

The sculpture was used in a mural by Diego Rivera depicting the history of Mexican medicine (1953-54).

Eduardo Paolozzi created a huge papier mâché replica, which he put in a traveling exhibition of his work (1988).

The Golden Idol in Steven Spielberg's Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) is perhaps the most renowned reincarnation of the statue.

A search on the internet uncovers a plethora of other creative works inspired by Aztec-style sculpture.

References And Further Reading:

- Evans, Susan Toby 2010 Ancient Mexican Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks, No. 3. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

- Grossman, Wendy A. 2008 Man Ray’s Lost and Found Photographs: Arts of the Americas in Context. Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 2 (1):114-139

- Hamy, E. T. 1899 Commentaire Explicatif. In Codex Borbonicus; Manuscrit Mexicain De La Bibliothèque Du Palais Bourbon (Livre Divinatoire Et Rituel Figuré), pp. 1-24. E. Leroux, Paris

- Hamy, E. T. 1906 Note Sur Une Statuette Mexicaine. Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris III (1):1-5.

- Walsh, Jane McLaren 2008 The Dumbarton Oaks Tlazolteotl: Getting beneath the Surface. Journal de la Société des Américanistes 94 (1):7-43.