How Prevalent Was Goddess Worship In Ireland?

Ireland has a long association with Goddess and water because to the fact that it is a nation entirely surrounded by the ocean.

Goddess' nutritious milk flows swiftly in springs, wells, lakes, and rivers, and it is no accident that civilizations first encountered her and flourished close to these water-rich areas.

To dwell near water meant to live close to the Giver of Life, where her secrets were accessible, as shown by Brigid's holy wells in Ireland, Sequana's Seine River in France, and Persephone's Lake Pergusa in Sicily.

The healing waters that flow from the holy locations where Goddess has manifested in her many forms are still being collected by devotees.

Examples include Artemis' epiphanies in Ephesus and the Mother Mary's apparitions at Lourdes and Knock.

Both Chalice Well at Glastonbury and Sulis Minerva's spring in Bath, England, flow in a tint of crimson suggestive of the Mother's holy life-giving blood.

Many English communities still choose to honor the hallowed waters with rituals known as "well dressings" that pay homage to their ancestors' pagan traditions.

Goddess as water is personified in some of these holy locations.

Goddess Worship At Castle Clonegal.

There is no museum, relic, or ruin to be found in the Temple of Isis at the 17th-century castle in Clonegal, Ireland.

In a maze-like maze of rooms under the castle, there is a functioning temple perched over a holy well.

The international group The Fellowship of Isis calls Clonegal Castle home, and rituals and rites are still performed there.

Under the direction of Lady Olivia Robertson, a 90-year-old founder of the group, they revere the Goddess in all of her manifestations.

In the middle of the 1970s, Lady Olivia, Lawrence Durdin-Robertson, and Pamela Robertson, his wife, formed the temple and organization.

In other regions of the globe, other leaders expanding the knowledge of goddess spirituality were also becoming more visible at this time.

Even when it was unfashionable for a woman to be a rebel, Lady O, as some of the Fellowship of Isis members refer to her, has always been a liberal and open-minded thinker.

She started researching esoteric sciences while still a popular author in the 1950s in order to use her innate psychic abilities.

She had always seen ghosts and angels, but in 1976, she had a vision of the goddess Isis, which surprised and perplexed her.

Despite the fact that her cousin Robert Graves (author of The White Goddess) was not well respected in the family or in what was considered "proper society" at the time, she was able to relate to their beliefs.

Scota, also known as "the black one," was an Egyptian Priestess of Isis and the daughter of the Pharaoh Cincris.

According to Lady Olivia and Lawrence, Scota was also a hereditary Daughter of Isis.

Following Olivia's encounter with the Goddess Isis in the middle of the 1970s, Pamela, Lawrence, and Olivia made the decision to convert their family castle, Clonegal Castle, into the headquarters of the Fellowship of Isis.

The Fellowship is prospering, with more than 20,000 members worldwide as of the time of this writing, despite the passing of Lawrence and Pamela.

The Noble Order of Tara was established by the Fellowship of Isis, or FOI, in 1990.

Its members were committed to promoting environmental causes.

They have other environmentally conscious initiatives going on and have been crucial in stopping strip mining on Mount Leinster.

The Druid Clan of Dana, named after the Irish Mother Goddess, was established in 1992 and is committed to the secrets of the Druids.

They arranged the 1993 Druid Convention in London via their publication, Aisling, which participates in the Council of British Druid Orders.

A second Goddess-oriented group, the Fellowship of Isis, was one of two that attended the Chicago-based World Parliament of Religions in 1993.

The Fellowship reveres all Goddesses, so why does Lady Olivia seem to connect with Isis the most? Isis is the global Goddess, the Isis of Ten Thousand Names, in her own words.

Demeter, Lakshmi, Kwan Yin, Dana, Ngame, and Mary are all mentioned by her.

As most Neo-Pagans could concur, Mary of the Christian faith was Isis to Lady Olivia.

After Osiris' resurrection, Christ was both Osiris and Horus.

In Lady O's opinion, the Goddess Isis is physically and spiritually appearing at this moment of universal change and the birth of the Feminine Divine.

As they return to the "old ways," millions of people all around the world claim to hear the Goddess calling.

These followers of the Divine Feminine believe that unless we once again value women and the Divine Feminine, the ecological, spiritual, and technical destruction brought about by a patriarchal society would eventually result in disaster.

Goddess spiritualists believe that Mother Nature's ultimate goal is to reestablish love and peace amongst all living things so that everyone may nurture and benefit from a healthy, bountiful way of existence.

The main sanctuary, naïve, Chapel of Brigid, and shrines honoring the twelve signs of the Zodiac are among the 26 shrines that make up the castle temple.

This is an illustration of what one would see when entering the shrines, but they do vary from time to time.

Devotees enter in procession through elaborately carved doors at the sound of a gong, and the Egyptian deity Thoth, protector of the secrets, stands directly in front of them.

A landing is reached by way of stone stairs. Goddess symbolism are seen everywhere.

There is a plaque with a picture of Jesus that is surrounded by further art that shows the Divine Feminine.

The main temple area, which is to the left, would be surrounded by sculptures of goddesses.

An iron gate leading to the historic castle well stands in front of you.

A large Tibetan bell that is used to signal entry into the Temple is located to the left of the gate.

The temple's interior, which is made of granite, measures 79 by 40 feet (24 by 12 meters).

There is a sizable sanctuary there, as well as nine stone pillars arranged in a row.

The sanctuary is surrounded by a short brick wall and two brick pillars that stand before the High Altar.

The clergy offer invocations on a modest elevated stone dais before the High Altar.

The High Altar of Isis serves as the main altar for all temple ceremonies.

The Fellowship of Isis commissioned gifted woodworker David Robertson, son of Lawrence and nephew of Olivia, to carve Isis of 10,000 Names as its centerpiece.

There are five primary chapels, each with characteristics of an element.

The historic Druidic well, which is 17 feet (5 meters) deep and known for its therapeutic virtues, is located within the Chapel of Brigid.

The Holy of Holies, also called the Chapel of Ishtar and devoted to the fifth element, Spirit, is reached via carved doors from Brigid's chapel.

Daily rituals and meditation are conducted at the temple as Lady Olivia assists in healing and attunes with members all across the globe.

The castle is situated next to a holy grove of trees in Ireland's stunning and verdant landscape.

The Fellowship of Isis, whose goal is to restore the Goddess to the world by whatever ways the Divine Feminine sees suitable, is still hard at work.

Rituals often include theatrical acts that impart knowledge of eternal secrets.

From a small group of three, the FOI's vision and goal have expanded to become a means for thousands of people to recognize and adore Goddess.

#How to reach Clonegal Castle.

Southeast Ireland's little town of Clonegal is home to Clonegal Castle.

Invitations are required for rituals.

Drop-in visits are not seen as appropriate manners, thus detailed instructions to the castle won't be given here.

Please contact Lady Olivia Robertson, Fellowship of Isis, Clonegal Castle, Enniscorthy, Ireland, if you would like further information on visiting Clonegal Castle.

The FOI operates lyceums and institutes both domestically and abroad.

On the Fellowship of Isis website, one may obtain details on the closest FOI chapter.

The FOI sells books and rituals that Lady Olivia has written in print and on audiotape, along with correspondence courses, a newsletter, and other products.

Goddess Worship At Kildare.

While it is exceedingly impossible to visit conservative, Christian Ireland without physically running across manifestations of the Goddess, travelers may experience at least four different facets of the Divine Feminine in Kildare.

Goddess-seekers may locate a Sheila-na-Gig, a Brigid-related holy well, a Brigid-related fire sanctuary, and the Brigidine Sisters known as the Sisters of the Solas Bride (pronounced breed).

Similar to Athena and the Roman Vestal Virgins, Celtic Brigid belongs to the category of Virgin Goddess (See Rome and Athens).

She is revered as a triple goddess and is the protector of smiths, healers, and poets.

As seen by her hallowed well and fire sanctuary in Kildare, Brigid is also a creative source of energy in her qualities of flowing water and blazing fire.

Interestingly, steam is created when water and fire come together; this is undoubtedly another source of unending strength and energy.

Her fire melts the smith's metal, and the water cools it to form the tools that will save humanity.

She has observable ties to her Neolithic origins via her affiliation with the benevolent female snake known as "the queen." Later, she became a part of Celtic Christianity and was elevated to sainthood as Brigid the virgin nun.

Because of this relationship, Brigid the Saint and Brigid the Goddess are revered as one by the Brigidine Sisters of Ireland, also known as Solas Bride.

The flame of Brigid is maintained by current nuns who continue the old custom.

Visitors may see the flame and take it home with them from their sacred location.

This is accomplished by lighting a candle from the Solas Bride's eternal flame and then passing the symbolic flame from one candle to another, wick to wick.

Miriam Robbins Dexter cites Geraldus Cambrensis in relation to the eternal flame of the Goddess and claims that the rivers Brigid in Ireland, Braint in Wales, and Brent in England were all given their names in honor of Brigid or Bride.

The final nun remarked to Brigid on the twentieth night, "Brigid, I have cared for your fire... and so, the fire having been abandoned...

it was discovered again, unextinguished." At the time of Brigid, twenty nuns were employed here to serve a master as a soldier, with she herself being the twentieth.

Brigid is described as "the female sage" and "Brigit the goddess, whom poets worshiped because her protective care over them was very great and extremely renowned" in Archbishop Cormac Mac Cullenan's Cormac's Glossary, written in 908 CE.

Brigid "originated at an era when the Celts worshipped goddesses rather than gods, and when knowledge – leechcraft, husbandry, inspiration — were women's rather than men's," according to Scottish academic J. A. Mac Cullock in 1911.

According to the forbidden shrine in Kildare, Brigid had female clergy and it was believed that males were not allowed to participate in her devotion.

Brigid became a nun and established a monastery in Kildare, a county renowned for its fertility and richness, according to Barbara Walker and Robert Graves.

They contend that like other components of society that the Catholic Church failed to abolish, they integrate.

They claim Brigit's bower was the center of an endless springtime where the village cows never ran dry and flowers and shamrocks sprung forth in her wake.

Brigid was compared to Mary by authors and poets who thought she was more than just a saint and was really the Queen of Heaven.

"Mother of my Sovereign," "Mary of the Goidels," "Queen of the South," "Prophetess of Christ," and "Mother of Jesus," according to Graves, are names given to Brigid.

According to Marija Gimbutas, Brigid was connected to childbirth like Artemis and Diana and served as the "midwife to the Blessed Virgin and thus the foster mother of Christ." Others compared Brigid to Tanit, the Heavenly Goddess, and June Regina.

According to Gimbutas, Brigid, the Greek Artemis Eileithyia, the Thracian Bendis, the Roman Diana, and the Baltic Fate Goddess were all prehistoric decedents of the life-giving Goddesses who survived Indo-Europeanization in the form of Nature, the giver of health, and in the guise of birds and animals.

Brigid was associated with weaving, spinning, twisting, and stitching, much like her European sisters, and it is stated that this women's activity must be halted on Friday, the holy day of the Goddess.

It's interesting that she was associated with Saint Patrick, who was allegedly a pagan before converting to Christianity.

Additionally, she was frequently mistaken for Brigid's early Pagan lover, Dagda, or "father," and was supposed to be a Christianized version of him.

Irish folklore holds that Saint Patrick is to blame for Ireland's lack of native snakes.

The account of Saint Patrick driving the snakes out of Ireland raises the possibility that the patriarchy subjugating Goddess spirituality is a metaphor for these linkages, as well as Brigid's connection to Neolithic snake imagery.

According to Gimbutas, local traditions include constructing snake effigies on Brigid's holy day of Imbolc, when "serpents are reported to come from the highlands." According to Walker, the twenty Brigid priestesses who were present in Kildare reflected the 19-year cycle of the Celtic "Great Year" She goes on to talk about how the Greeks made references to Apollo going to the "temple of the moon goddess" (Brigid) every nineteen years in their stories.

Around the Stonehenge circle, markers were placed to designate these Great Years.

According to researcher Patricia Monaghan, Brigid is linguistically related to Bridestones, also known as sarsens, which are the large sandstones used to build Stonehenge.

This suggests that Brigid was known in early Neolithic, pre-Celtic periods.

In addition to the Thuggees of Kali and the "Assassins," who revered the Arabian Moon Goddess, Walker mentions another part of Brigid related to martial arts and her warriors known as brigands as an example of a goddess's follower becoming vilified.

Brigid, also known as Brigantia in England, Bride in Scotland, and Brigandu in Celtic France, has many distinct names.

Patricia Monaghan, a scholar, presents a somewhat different story of Brigid.

In this mythological cycle, Brigid is the human offspring of a Druid who was subsequently canonized and baptized by Saint Patrick.

It was said that the Christian Brigid had many of the same traits and abilities as the Goddess Brigid, and that the abbess had exceptional authority to choose bishops who had to be goldsmiths.

Imbolc or Candlemas, Brigid's feast day on February 1st, was a celebration of the "lactation of the sheep, symbolic of new life and the approach of spring," according to Gimbutas.

She claims that a milk libation was thrown into the Earth and connects the life-giving material to Brigid's flower, the dandelion, which when crushed generated milky juice, supplying sustenance for the young lambs.

Anyone who has experienced the gloom of Ireland's winters understands how uplifting it is to start to glimpse the light again, the symbolic fire of Brigid.

This festival also commemorates the return of the light as the world emerges from the winter's darkness.

This was a joyful period of processions, singing, dancing, and ceremonial baking.

Gimbutas asserts that "honoring the Bride, giving presents, crafting dolls, preparing special cakes, greeting the Saint in every home, and anticipating her presence as a blessing must have roots deeper than the final decades of paganism; much of it carries on Neolithic customs."

Brigid's fire sanctuary in Kildare is described by Rufus and Lawson as a "low stone wall, rectangular and not round as in ancient times."

The recreated shrine is neat, orderly, and quiet, speaking nothing of its past existence as a spiritual center for Irish women, both during the Goddess' lifetime and for centuries following.

In the heart of Kildare, in the graveyard of the Cathedral Church of Saint Brigid, is where you'll find Brigid's Fire House.

Before leaving the church, look inside for the Sheela on Bishop Wellesley's tomb from the 16th century.

It is beautifully placed below the left-hand corner of the top slab and above a panel depicting the Crucifixion.

The Sheela's legs are split, and her pubic hair is visible.

The Tobar Bride, also known as Brigid's Well, is a mile or so from the fire sanctuary.

With a statue of Saint Brigid dressed as a nun and a natural well of healing waters, the holy site suggests that it is equally dedicated to the Saint and the Goddess.

The brick arch that crosses the holy stream-like well is decorated with Brigid's pagan emblem, the Cross of Brigid.

Don't forget to bring a container so you may transport the restorative waters of Bride home.

Votive gifts, such as rags or pieces of fabric fastened to trees (sometimes referred to as clootie trees), are often left at the location.

In accordance with Gimbutas, who cited Wood-Martin, "The rag or ribbon, removed from the clothes, is thought to be the storehouse of the spiritual or physical maladies of the suppliant.

Rags are riddances rather than just offerings or votive objects.

(In another type of riddance ritual, the matriarch of the house would distribute to family members a strip of cloth called the brat Brighide, or Saint Brigit's mantle, which was hung on a tree or bush a few days before Saint Brigit's Eve to protect the family from illness or misfortune in the upcoming year.)

The healing properties of Brigid's waters have been known since Neolithic times, which helps to explain why numerous wells under Mary-related churches and temples (such as those at Clonegal, Chartres, and Lourdes) may have retained their reputation for miracles.

It was believed that a few of the goddesses' holy wells may increase a woman's fertility.

Devotees would go to the wells on the first day of spring to undertake purification rituals, including washing their hands, faces, and feet, removing strips of cloth from their garments, walking around the stone, praying, chanting, kneeling, and sipping from the holy waters.

They might then go to "a river stone which has footprints," where they would continue to pray, according to Gimbutas, who is quoting Wood-Martin once more.

Footprints may be observed carved into the stone near the holy waters at Tobar Bride.

Brigid the Goddess and those who honor her are warmly embraced by the nuns of the Church known as the Sisters of the Solas Bride.

You are welcome to visit their refuge, but only with previous preparations.

The Sisters welcome individuals and groups and have joyfully accommodated and shared ritual space with small groups of committed practitioners of Goddess Spirituality.

Interested parties will be needed to make personal contact to organize a visit.

How to get to Kildare?

Kildare is conveniently accessible by rail, bus, and private vehicle and is situated 32 miles (51 km) southwest of Dublin.

If you're driving, use the N7 Dublin-Limerick Road to the Kildare Cathedral, which is in the town's center.

One mile south of Kildare is where the well is situated.

Following the directions out of town toward the Japanese Gardens, there will be a sign directing drivers to the Tobar Bride down a tiny road to the right approximately 300 yards (270 m) before you arrive at the Gardens.

Goddess Worship At Newgrange.

Another marker pointing left down the path will be located around 100 yards (90 m) farther; this sign will direct tourists to the well at Newgrange.

The great megalithic tomb of Newgrange is ranked alongside the temple of Ggantija in Malta as one of the most impressive prehistoric monuments in Europe, according to any old guidebook, but mainstream scholars are still divided over how to interpret the significance of this magnificent Goddess site constructed more than 5,000 years ago.

According to some experts, the imagery found on Western European megalithic art is connected to altered states of consciousness.

The altered states may sometimes be brought on by using hallucinogens, and they can also be brought on via shaman trance dances.

When they find the controversial archaeologist Marija Gimbutas' work compelling, many goddess proponents depart from conventional thinking.

Even Marija was unable to pinpoint the precise events that took place at Newgrange, but Gimbutas' decades of research into Neolithic archaeology and the significance of artwork and artifacts in a cultural and religious context have given passage graves like Newgrange a fuller and richer meaning.

Advocates contend that Newgrange was a holy location for the Goddess and that its artwork symbolizes concepts of birth, death, and rebirth, with the passage grave serving as both "womb and tomb," based on the graphic language she invented, folk literature, and a little amount of intuition.

"The heart of the religion of the Goddess in the British Isles," according to author Peg Streep, is Newgrange.

It is without a doubt a location for ritual, processions, and significant gatherings that are suggestive of the early Neolithic builders' religion!

Many claim that Newgrange is the best example of a passage grave in Western Europe.

Carbon-dating research suggests that it was constructed around 3200 BCE.

Farmers who kept livestock were the people who constructed Newgrange.

They used stone as opposed to metal to create this complex edifice, which required not only extraordinary labor but also knowledge of design and engineering.

They also watched and analyzed astronomical movements.

It measures 265 feet (81 meters) in circumference and 45 feet (14 meters) high.

Only 12 of the 35 standing stones, or menhirs, that previously surrounded it are still standing.

According to Streep, this circle may have served as a barrier between the mother's womb's holy area and the rest of the world.

Although the mound is now covered in grass, many academics believe that white quartz once covered it.

The quartz would have significance beyond just aesthetic value since it was a rare stone that had to be imported from a distance.

Gimbutas compares the mound to the world's cosmic womb or egg, and the white coating was designed to resemble an egg's shell.

For the construction of Newgrange, an estimated 180,000 tons (163,080,000 kg) of stone were needed.

The entrance to the mound faces the dawn in the middle of winter.

The 62-foot (19-meter) long tube leads to a central room from which three side chambers branch out.

On the midwinter solstice, sunlight streams into the chamber via a roof box lintel at the entrance.

During the solstice, the sun can be seen slowly filling the interior passageway until it reaches the back chamber and illuminates a carving of a triple spiral that some people think represents the Goddess.

A symbolic (or literal?) rebirth and regeneration of the dead may result from this, as well as the effect of awakening her powers.

Before moving back down the entrance passageway and leaving the mound in complete darkness once more, the light briefly fills the cavern.

It has been speculated that this dramatic effect might have been performed using a polished mirror at other significant times throughout the year, but that is just conjecture.

Gimbutas thought sacred symbols and patterns that recurred all over Neolithic Old Europe were used to invoke the Goddess.

According to Streep's citation of Gimbutas, "ritual action" served as a means of "communicating with the divine" and an invocation of the Goddess' enshrined regenerative abilities.

The art's iconography includes the ideas of life, death, and regeneration, which are all aspects of the Goddess.

The imagery of the owl and snake—symbols of rebirth and rebirth—represented these ideas.

These theories are further supported by the structure's orientation and commanding position close to the Boyne River's (named for the Goddess Boand) bend.

Even if some of the pictures are more abstract, when they are studied across all of Europe, a language and a unified iconography start to take shape.

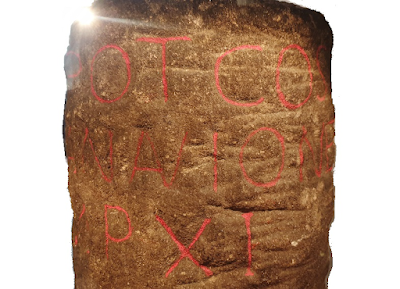

The stone near Newgrange's main gate is vividly engraved with three snake coils, which stand for three sources of life.

Similar to Neolithic Catal Hüyük, iconography starts to emerge in three-groupings.

The brow ridge of the Owl Goddess, stone basins, engravings of triple snake spirals, coils, and cartouches, as well as side cells at Newgrange, are all discovered in triplicate.

Gimbutas can identify the large snake coils that are inscribed on orthostats and are connected to V, M, chevrons, and zigzag bands.

She postulated that the presence of arcs, wavy lines, bands of zigzags, and serpent shapes indicated a belief in the reproductive capacity of water as well as a relationship between the snake and the strength of stone.

Triangles are depicted on the walls and curbstones of Newgrange.

Sometimes they are by themselves, other times they are in rows and pairs linked at the tip or the base, or they are encompassed by arcs.

These pictures are of the Goddess of Death and Regeneration, according to Gimbutas.

Her interpretation of the "serpent ship" motif connected to the religion of the dead is particularly intriguing.

At Newgrange, the union of zigzags or winding serpents (symbols of renewed life) with triangles or lozenges (both special signs of the Goddess of Regeneration) creates abstract images of "serpent ships," which can be taken literally to mean ceremonial ships connected to death rituals that carry the dead toward renewal.

Gimbutas describes spheres and snake coils representing a full moon, opposed crescents alone or with a snake coil in the middle depicting a moon cycle, and wavy lines of winding serpents measuring time as additional indications of time and lunar movements in the stone carvings at Newgrange.

She claims that up to thirty winding snake turns corresponded to a near approximation of the lunar month and that serpentine patterns with fourteen to seventeen turns signified the number of days the moon waxes.

It is possible to speculate that Neolithic practitioners included both of these elements in their death ritual because the structure is linked to death and rebirth and contains imagery that is both reflective of sunlight and water.

This brings discussions back to folk literature mixed with some whimsy.

The study of Roman literature, figurines, and inscriptions has revealed what is known about ancient Ireland.

What before is mostly unknown since Celtic literature did not become widely read until the second century CE.

It is widely acknowledged that Brigid represented the elements of fire and water (or light), as well as connections with the serpent, whose history dates back to the Neolithic era.

In light of the fact that the rituals performed at this particular mound are beginning to comprehend and revere her imagery and essence, perhaps we should take a moment to consider how she might be related to Newgrange.

We should also keep in mind that according to folklore, the god Dagna, who is occasionally referred to as Brigid's consort, constructed Newgrange for himself and his sons.

What if this is just a patriarchal interpretation of the story? It is entertaining to speculate if Dagna really did construct Newgrange as a spectacular expression of his love for his consort, much as Ramses did when he constructed the Taj Mahal or the little Temple of Hathor at Abu Simbel in honor of his great love Nefertari.

According to a different piece of mythology, Bru na Boinne, the Gaelic name for the area near Newgrange, means "the house of the Goddess of the River Boann."

It claims the River Boyne, also known as Boinn or Boand, is named after the Goddess Boand and is located close to Newgrange (she of the white cows).

Boand, who is regarded as one of the main Earth Goddesses of prehistoric Ireland, is the embodiment of the abundance and vitality found in water, or the nourishing milk that flows from a revered cow.

Boyne, its modern Celtic name, which translates to "illuminated cow," is transliterated as Buvinda.

Additionally, the Celtic term denotes brightness, whiteness, and knowledge.

The wise salmon, along with other fish connected to the Goddess, dwells in the River Boyne.

Perhaps in Newgrange, in a manner similar to Eleusis, the priestesses and priests of the Goddess taught their people the lessons of life and death while performing ritual.

According to legend, Boann and her partner Elemar were Newgrange's original residents until Elemar was replaced by Dagna, which leads us back to Brigid.

Could Boann have been a younger version of Brigid? We already know that Brigid inspired the naming of rivers.

Since Brigid is a Goddess of Healing, the River Boyne was also praised for its therapeutic properties.

There are undoubtedly no concrete solutions, but many connections cause cultural diffusionists to pause and give a thoughtful "ah-ha." # How to get to Newgrange.

About 6 miles (10 km) west of Drogheda, in the Boyne Valley, which is located to the south of the N51 Drogheda–Navan Road, is where you'll find Newgrange.

From Drogheda, you may go to Newgrange by train or bus.

On the nearby road to Slane, you can find the Knowth and Dowth mounds.

Within the Bru na Boinne complex, there is also a prehistoric ritual pond made by humans called Monknewtown that might be worth a look.

If you're traveling by car, think about taking a day trip from Dublin, which is 45 km (28 mi) south of the site.

There is a visitor center on site, but it is advised to call ahead because there has been discussion about restricting access to Newgrange's interior.

Much of the discussed imagery can be seen by simply walking around the grounds.

The tremendous feeling of the sun entering the chamber is reenacted by guides using a flashlight to give tourists some idea of the event, but it is almost impossible to be within the mound on the solstice since individuals are wait-listed for years to enjoy the privilege.

It could be a good idea for travelers to have a small container with them so they can gather water from the River Boyne.

Worship Of Goddess Sheila-na-Gigs.

Stone carvings of female genitalia known as Sheila-na-Gigs, also known as Sheelas, are typically found on the walls and doorways of Celtic churches and monasteries in Western Europe and the British Isles, though they can also be found in Indonesia, South America, Australia, Oceania, and India.

The real role of Sheelas is not clearly known, however most say they were icons or symbols of protection, much like the guardian gargoyles on Gothic cathedrals or the gorgon on Athena’s shield.

This author concurs with that assertion and suggests that the sign could have stood for the idea that being within the building on which the Sheela is carved is equivalent to entering the holy vulva, a portal leading to the protection of the Mother Goddess' womb.

The figures' stance of sitting, reclining, or standing with legs akimbo and completely exposed yonis has been suggested as a potential emblem of exhibitionism, however that hardly seems plausible given that they were discovered carved in hallowed locations.

In addition to raising the intriguing hypothesis that Sheelas are connected to Celtic or pre-Celtic forms of Oriental and Mediterranean holy prostitutes, Rufus Camphausen has also indicated potential ties to Baubo and Ama-no-Uzume.

He suggests the term nu-gag, which refers to "the pure and immaculate ones" and was used to describe the sacred temple prostitutes of Mesopotamia, as a potential linguistic indicator of the Sheila-na-Gigs' earliest forms.

Sheelas are often found with the carved portion of the yoni worn by the contact of several hands, probably made in respect or prayer.

It reminds people of fertility symbols, which some cultures think, if touched, may bring forth plenty and procreation.

The Sheela, according to author Shahrukh Husain, is connected to the goddess Brigid of the Celts, and she may have represented the "split-off of the sexual aspect of a virginal goddess."

Archaeologist Marija Gimbutas compared the spread-legged prehistoric Frog Goddess, the frog-headed Egyptian Goddess Haquit (Heket), and the ancient Greek goddess Hekate, known as "Baubo," or toad, to Sheelas.

Gimbutas asserts that the names for toads in European languages include the connotations of "witch" or "prophetess," and that the toad "was incarnated with the powers of the Goddess of Death and Regeneration, whose duties were both to bring death and to restore life."

At an archaeomythology symposium in Madouri, Greece, Professor Joan Cichon reports scientists Miriam Robbins Dexter and Starr Goode think the iconography of the Sheelas resemble the “Sovereignty Goddess” of the ancient Irish.

Some modern ladies have been turning up their noses at traditional taboos and embracing the brazen iconography of the Sheela to indicate their empowerment, sexual liberty, and knowledge of their connection to the Goddess.

~Kiran Atma